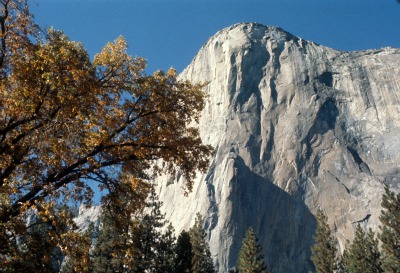

The Yosemite Indians...

And How They Lived Their Lives

What Did They Eat?

The Yosemite Indians had no knowledge of cultivation...they didn't need it. The food supply furnished by native plants, animals, birds and insects afforded them a healthy and varied diet.

For meat they killed deer and smaller mammals as well as birds. Fish was also a large part of their diet.

They also ate acorns, berries, pine nuts, edible plants, bulbs, mushrooms, fungi, larvae of ants and other insects. What they ate was largely dependent upon the season.

But without a doubt it was the acorns of the Black Oak, rich in nutritious vitamins, that constituted their "staff of life."

Gathering the acorns and then storing them in the granary the

Yosemite Indians referred to as a chuck-ah was just the first step.

This

was followed by a complicated process for the preparation of acorn mush

and bread that the Yosemite Indian women accepted as a matter of

routine.

At first glance the chuck-ah, a large cylindrical

basket-like structure, appears to be the clumsy nest of some extinct

giant bird.

Four slender poles of Incense Cedar about eight feet

in length were arranged in a square. A center log, about two feet in

height, formed the bottom of the chuck-ah, and together they formed the

frame support.

The basket-like interior was of interwoven

branches of deer brush (Ceanothus) tied at the ends with willow stems

and fastened together with wild grapevine.

This basket was then lined with dry pine needles and wormwood. The wormwood was effective in discouraging the invasion of insects and rodents, and was found growing abundantly in the region.

Once the chuck-ah was filled with the acorns gathered that fall, it was then sealed with more pine needles, wormwood, and sections of Incense Cedar bark that were bound down firmly with wild grapevines to withstand the coming winter.

The finishing touch was to thatch the exterior with short boughs of White Fir or Incense Cedar, (making certain that their needles were pointing downward to shed snow and rain), and finishing by fastening them securely with bands of wild grapevine.

How Yosemite Indians Prepared Acorn Mush

After cracking and shelling, the bad acorns were discarded, and the kernels were pounded into a fine yellow meal.

Over time, mortar holes were worn into the granite from this grinding.

"Grinding-sites" may be found at every village location where Yosemite Indians lived around the park...if you know where to look.

In order to remove the bitter tasting tannin from the ground meal, leaching was required. In this process the acorn meal was placed in a specially prepared hard-packed sand basin.

At regular intervals, warmed water was poured over the acorn meal and allowed to seep through the sand beneath. Many repeated applications of increasingly warm water were necessary to completely remove the natural bitterness of the acorn.

Three products were obtained during the leaching process dependent upon the "fineness" of the meal.

The finest meal became a gruel or thin soup, and the middle consistency was used for mush. The most coarse meal was formed into small patties that were then baked on hot, flat rocks. These were a favorite of the Yosemite Indians.

The mush was cooked in traditional large cooking baskets where the heat for cooking the mush was provided by gently lowering hot stones into the cooking basket by means of long wooden tongs.

Once the mush was cooked, tongs were used to remove the stones and they were quickly dropped into cold water. The mush on the stones congealed in the cold water and could then be peeled off and eaten as a special treat.

Insect Snacks

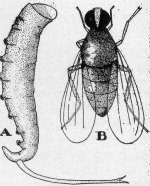

Ka-cha-vee, An Insect Snack. (a) The pupa, was a favorite snack of the Yosemite Indians. (b) The Adult Fly (Ephyd Tahians)

One of the most important articles of trade between the Mono and Yosemite Indians was the insect delicacy known as Ka-cha-vee, a peculiar insect pupae which comes from the saline waters of Mono Lake... breeding there in huge numbers.

The waves of Mono Lake cast upon its shore, millions of the dead bodies of these undeveloped flies.

The Mono Indian women would then scoop them up into large baskets. Once the smelly mass was thoroughly dried, they rubbed them to remove the skins.

After still further drying, the Ka-cha-vee were packed for enjoyment later during the winter months...having the flavor of a mild shrimp.

Another prized food product which the Mono Indians traded with the Yosemite Indians were the caterpillars of the Pandora moth.

These were known in the Indian tongue as Peaggi and were collected in the Jeffrey Pine forests just east of Yosemite National Park.

At a certain time known to the Mono Indians, the caterpillars left their home in the trees hoping to enter the ground to form their pupal cases.

But shallow trenches were dug by the Indians in the loose soil around the trees where the Peaggi became trapped.

The women visited these traps regularly and collected the caterpillars that had accumulated there. They were then dried and stored away for cooking into stew.

Grasshoppers and the larvae of yellow jackets were both a favorite snack, and were roasted to a “crispy perfection” in earthen ovens.

Food Gathering And Preparation

Miner's Lettuce was eaten raw, but often red ants would be allowed to run over the leaves to flavor them with formic acid... giving it a nice “vinegary” taste.

The shoots of the Brake Fern, which commonly grows in most moist, shaded regions of the valley floor and canyon walls, were harvested when the fronds were in the most tender uncurling stage.

After removing their "hairiness" by scraping, they would be eaten raw or could be cooked if they preferred.

Clover was eaten without preparation when the plants were young and tender just prior to their flowering stage. To prevent indigestion, California Bay nut was often munched along with the clover.

Lupinus bi-color, as well as other species of the lupine family made good greens, especially when moistened with manzanita cider.

Bulbs

Various kinds of bulbs were such an important part of the diet of the Yosemite Indians that one group within the tribe became known as "Diggers" to the early California settlers.

The bulbs that made for especially good eating were those of the "Squaw Root", and the various brodiaeas, especially bulbs of the Harvest Brodiaea, and Camass.

To prepare them, bulbs were baked in an earthen oven where:

First the pit was dug, and a layer of hot stones were placed in the bottom of it. These were then covered with leaves. A layer of bulbs was next...followed by alternating layers of leaves and stones, then leaves and bulbs until the pit was full.

Finally over the top, dirt would seal the oven, and a fire was built on top.

The bulbs were allowed to bake over night.

Mushrooms

Mushrooms are in season in Yosemite during April and May, and were usually shredded and dried or boiled and eaten with mineral salt, or as a soup.

Berries

Manzanita berries, are smooth-skinned and have an agreeable acidic flavor. They were usually eaten raw, but could be made into cider for drinking directly or for mixing with other food preparations.

In making the cider, berries were placed in a basket and crushed into a coarse pulp. Gradually water was added and allowed to drip into a watertight basket beneath. As the water seeped through the pulp, the berry flavors were captured.

Other favorite berries of the Yosemite Indians were wild raspberries, thimble berries, wild strawberries, currants, gooseberries, squaw berries, and wild cherries.

Ways of Preparing Fish and Game

Fresh meat was usually broiled on hot coals, but could be roasted before the fire. Sometimes it was baked in earthen ovens.

For consumption during the winter, meat was dried into long, thin strips by hanging exposed to the air and sunlight. It was sometimes cured instead on racks above small fires.

Squirrel, rabbit and fish were often roasted directly on the coals, or amongst the hot ashes.

To make cooking more rapid, the animal itself was sometimes stuffed with hot coals before roasting.

Eating the Acorn Mush

At meal time, the Indian family gathered around the prepared basket of acorn mush. Using the first two fingers as spoons, the family would dip from the same basket.

Sometimes instead with finer mush, a single finger was twisted around and around as with the Pacific Islanders when they are eating poi.

Manzanita cider, was served as an appetizer, and was usually enjoyed by dipping a small stick with feathers fastened to one end into the beverage, and then sucking the drink from the feathers.

A small, tightly-woven basket "dipper," was also used sometimes when drinking.

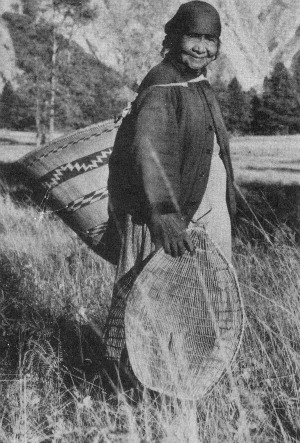

The Art Of Basketry

Julia Parker is a National Treasure. She has been demonstrating the art of Indian Basket Weaving in Yosemite National Park for well over 60 years. In 2004 Public Broadcasting Station KQED produced a short video featuring Julia where she talks about her basket weaving and her heritage. You will enjoy it...view it here:

Many different native plants were utilized as material by the Yosemite Indian woman when making the baskets that she would need.

Willow, squaw bush, red-bud, tule-root, maiden-hair fern, brake fern, wire bunch grass and the red strips of bark from the Creek Dogwood were some of the most common sources.

She knew the names of all the "basket material" plants, where they could be found, and the proper time of year to gather them.

But finding and gathering the proper plant material was only the first step in the process of basket weaving. The proper preparation of these materials was of equal importance.

Peeling and trimming to the correct width, fineness and length, and then either soaking in cold water, boiling in hot water or burying in mud...her knowledge of the process was key!

Each basket was designed with a specific purpose in mind. A good example is the large conical shaped basket designed for carrying heavy burdens...most often acorns.

It was known as a “burden basket”, and was supported on the back and secured by a strap usually passing over the forehead.

Another specialized basket used by the Yosemite Indians was the mush-bowl baskets which has already been mentioned.

Small, closely-woven “general purpose” baskets were also used for serving foods.

Tightly woven disc-shaped baskets were used for winnowing wild oats and other seed plants.

Dipper baskets were small and tightly woven devices designed for holding liquids and drinking.

Cradles, of openwork basketry were woven and then covered with deer skin for carrying the papoose. The Yosemite Indians referred to this device as a "hickey".

Special ornately designed baskets were woven specifically for use in wedding and dance ceremonies.

For food harvesting, basket weirs were used by the Yosemite Indians for catching fish. Woven seed beaters were used for beating seeds into carrying baskets.

How The Baskets Were Woven

A twining and coiling method was commonly used by Yosemite Indian women in weaving their baskets.

The "twined basket", is made with a heavy foundation that is vertical from the center to the rim...the woof being of lighter material.

In the "coiled basket", the heavy foundation is laid in horizontal coils around the basket with the filling running in spirals around heavy twigs.

Within the larger Miwok tribes, the most common twined baskets were the burden basket, the triangular scoop-shaped basket used for winnowing, the elliptical seed beater, and the baby carrier or “hickey”.

A special application of soap-root was used to make the burden baskets more seed-tight, and when it dried, it would harden into a thin but brittle coating.

The fibers from the dry outer layers of the soap-root were commonly used as scrubbing brushes for cleaning the cooking baskets.

For design colors, the roots of the brake fern were boiled to obtain a black dye; red-bud produced red.

Before she started her basket, the Yosemite Indian woman had to know exactly where to begin each figure of the design. And as the bowl of the basket continued to flare, the size of each figure had to be increased accordingly.

Considering that she was working entirely without directions, the design, color, and mathematical accuracy of her finished baskets is a superb example of fine art.

Weapons

The bow and arrow was the principal weapon for both hunting and warfare, and in the hands of a skilled marksman could kill out to fifty yards.

Like the Indian woman weaving her baskets, the Indian brave displayed great skill fashioning his bows and arrows.

Either Incense Cedar or California Nutmeg were used for the wood of the bow. When cedar was used, the Indian craftsman knew that it was necessary for the wood to be treated for several days with deer marrow...preventing it from becoming brittle once dried.

The bow was normally three to four feet long, was backed with sinew for added strength, and had re-curved ends. The glue that was used for applying the sinew to the back of the bow was made by boiling deer bones and combining that with pitch.

A plain bow without the reinforcement of a sinew backing was fine for hunting small game at closer ranges, and twisted sinew made the best bow strings.

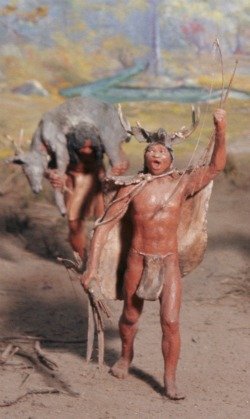

Deer were commonly stalked by hunters disguised by deer skins. By imitating the movements of the deer, a skilled hunter draped in deer skins could often approach near enough to his prey to make a successful shot.

When more than one deer was desired, the Yosemite Indians would either drive the deer herd into an awaiting ambush, or into traps made of nets.

The Yosemite Indian brave designed the arrows for his use on large game in two parts. The shaft had a detachable fore-shaft which remained in the wound, causing catastrophic bleeding leading to a quicker death.

The arrow shafts were usually fashioned from syringa or sometimes wild rose.

First the bark would be removed, and the wood stripped and trimmed to an even thickness. The arrow shaft was then straightened further with stone tools, and the last step was to polish the arrow shaft with a scouring rush.

Feathers and obsidian arrow points were then attached. Feathers was split down the middle, and the four half feathers were attached to each shaft with a wrapping.

Obsidian arrow heads were then fitted into slots in the end of the shaft, held in place by sinew wrapping and pitch.

Obsidian is a type of volcanic glass and produces razor sharp edges. It was the material of choice for the manufacture of arrow heads and other cutting tools.

Obsidian was most often obtained from quarries in the Mono or Owens Valley region. It was a valuable trade article of the Mono Piutes, who periodically visited Yosemite Valley to trade.

The Yosemite Indians themselves would occasionally make journeys across the Sierra in search of obsidian. Pieces of obsidian suitable for working into tools were picked up off of the ground or were broken from larger masses of it.

The smaller pieces intended for arrow points were broken from the rock of obsidian by striking it sharply and skillfully with a tool called a hammer-stone. In this operation the obsidian rock was held in one hand, and the hammer-stone in the other.

The flakes of obsidian that were obtained by hammering would then be shaped further by a tool of deer antler. The arrowhead was then finished and sharpened by removing even smaller chips along the edges of the point with a smaller antler implement.

With the obsidian grasped in the palm of one hand and protected by a buckskin pad, pressure was exerted on the edge of the arrowhead with the sharp end of the antler tool and these were chipped to an incredible sharpness.

Fishing

Fish were gathered by the Yosemite Indians by spearing using a wooden shaft fitted to a bone point. One end of a small cord was securely attached to the point and the other was held in the fisherman's hand.

Once struck, the struggles of the impaled fish freed the point from the shaft, and the fish was landed by the fisherman with the cord.

Fish were also captured with weir traps that were made of long willow sprouts woven together and closed off at a pointed lower end.

The weir traps were placed in dams constructed especially for that purpose, and were elevated above the surface of the water and below the dam. As they swam downstream, the fish would enter the trap, becoming caught at the lower end of it and out of the water where they could be easily retrieved.

When water levels were low enough during the summer months, the Yosemite Indians used pulverized soap-root, mixed with soil and water to stun the fish.

This mixture was rubbed on rocks in the stream where the action of the water would make it foam.

The fish would experience oxygen starvation, and rise to the surface of the water where they could easily be captured by the Indians with their scoop baskets.

Yosemite Indian Bone And Antler Implements

Bone and antler tools were used by the Yosemite Indians for making various other tools and implements. For example certain deer bones became awls that were used for weaving coiled basketry.

The limb bones of the Jackrabbit and Sierra Grouse provided whistles that were used in ceremonial dances, and as we discussed, deer antler points were used for the shaping and finishing of flint and obsidian arrowheads and knife blades.

Antler implements were also used for extracting acorns stored in holes by woodpeckers. Split deer leg bones became scrapers for use in shaving wood when making bows, and for removing hair from hides.

Yosemite Indian Clothing

Wild animal skins furnished the only materials suitable for clothing. In the warm summer months the Indian men wore nothing but a loin cloth of buckskin. The Indian woman wore buckskin skirts, reaching from their waist to their knees. Children usually went unclothed in the warm weather until they were about ten.

Blankets made from the skins of deer, bear, mountain lion, and coyote, were used by the Yosemite Indians as wraps in cold weather. A favorite blanket was made by weaving narrow strips of rabbit skins into a soft and very warm covering. The blankets that were worn were also used as bedclothes.

The moccasin, was the only footwear, and was worn primarily in the cold weather, or when making trips in rough country. Made of buckskin, the moccasin was fashioned in one piece, and then was lined with shredded cedar bark. Seamed up the heel and the front, it was stitched using milkweed fiber thread.

Over-lapping pieces of hide would often be secured around the ankle.

At mourning and dance ceremonials, the Yosemite Indian man would wear a head-dress of magpie feathers tied with sinew. With this was worn a head-band of tail feathers from the red-shafted flicker.

Straps of eagle down draped over one shoulder and the chest, and was tied around the waist. Wild-cat skin kilts completed the costume.

How Their Hair Was Worn

Adult Yosemite Indians wore their hair long...often to the waist. It would either be allowed to flow freely, or might be tied at the back of the neck with a feather rope. Flowers and feathers were regularly worn in the hair as adornments.

The hair was cut short when in mourning and this was accomplished using an obsidian knife.

Yosemite Indian Shelters

The Yosemite Indian dwelling was the conical shaped u-ma-cha.

These was constructed by placing ten or twelve foot long poles in the ground around an area measuring about twelve feet in diameter. The tops of the poles were then inclined together.

Over the framework, slabs of Incense Cedar bark would then be placed.

The u-ma-cha was easy to build, was waterproof, and was easily warmed. The south facing entrance could be closed with a portable door.

There was an opening at the top of the structure to allow smoke to escape from the fire in the middle of the dwelling. A single Yosemite Indian u-ma-cha could house a family of six, all their worldly possessions, and the dog.

During the summer months, the Indians lived outside of the u-ma-cha in brush arbors, and the u-ma-cha was used as a storehouse.

Other common Yosemite Indian structures included large earth-covered round houses built especially for ceremonies, and smaller earth-covered sweat houses used cleanliness and curative practices.

Yosemite Indian Customs and Ceremonies

The more than thirty Indian villages on the floor of Yosemite Valley were clearly divided into two groups, physically divided by the Merced River.

This practice was in accordance with the Miwok Indian principle of totematic division where the Indians classified everything in nature as belonging to either the land or to the water side.

The Grizzly Bear was the symbol of the land side, and the Coyote of the water side. This division was not only of the Indian groups themselves, but of all other objects as well.

It was the Yosemite Indian custom for a man to marry only into the opposing division. In this manner in-breeding was kept to a minimum.

In the Yosemite Valley, members of the Grizzly Bear group lived on the north side of the Merced River...members of the Coyote clan lived on the south side.

"Yosemite" means Grizzly Bear, and it soon became the name used by those living outside the valley for all of Chief Tenaya's people rather than for just those living north of the river.

Death and Mourning

Yosemite Indians used cremation as a means to liberate the spirit of the dead. The belongings of the deceased were usually burned at the cremation, with the exception of several items that were reserved for the annual mourning anniversary.

The mourners, while dancing and crying, often threw gifts into the flames as an offering of respect. Once the body had been consumed, the remains were gathered up and buried.

The widow would either cut her hair short or it was burned off. As a further symbol of grief, she would smear her face with an ointment of pitch and ash from the cremation, as did the other female relatives.

The mixture would cling to the face and clothing for months, and it was disrespectful to wash it off.

In the late summer or autumn of each year, the Yosemite Indians remembered their dead with a mourning ceremony. For several nights there would be weeping, wailing, and singing around the campfire.

At the dawn of the last day of the ceremony, mourners threw food into the fire to feed the spirits of the dead. Those who had lost loved ones during the year fed the fire with the remainder of the deceased's belongings saved from the cremation ceremony.

As a symbol that the period of grief and its restrictions were over, the mourners carefully cleansed themselves with water.

The Ceremony of Thanksgiving

The Yosemite Indians also celebrated their own form of Thanksgiving...a symbol of gratitude shown toward "Coyote Man," an important diety of their Miwok Indian mythology.

For three days and three nights the dancers performed the acorn dance and fasted. On the fourth day squaws prepared the acorn mush and other foods for the feast.

All those participating in the feast then joined in dance, moving slowly around the fire in a large circle, chanting and shaking their rattles over the flames.

As this was concluding, one of the women would spread acorn gruel in four successive circles around the edge of the fire.

The intent was for this to burn and be carried into the air in the four directions eventually, to be eaten by the spirits of the dead. The Yosemite Indians did not eat from the new acorn crop until the spirits had been satisfied.

After feasting, dancing continued far into the night. A fire dance was performed as a tribute to the fire that heated the cooking stones...then a stone dance was performed in appreciation of the stones that when heated cooked their acorn mush.

At the conclusion, a "basket dance" was performed honoring the baskets which held the mush.

An acknowledgement is in order:

In July of 1941 a Special Issue of Yosemite Nature Notes was published entitled "Yosemite Indians".

Written by Elizabeth Godfrey with the help of Junior Park Naturalist James E. Cole, M.E. Beatty...an Associate Park Naturalist, and Park Naturalist C. Frank Brockman, it incorporated most everything that was known about the Yosemite Indians at the time into one small booklet.

This webpage has followed the outline of the booklet and has used a lot of the text...(though written in 1941, there has been a need for quite a lot of updating and editing as well).

The photos featured here are largely from other sources as noted.

Julie and me. March 2014

To return to the Homepage From Yosemite Indians please click here.

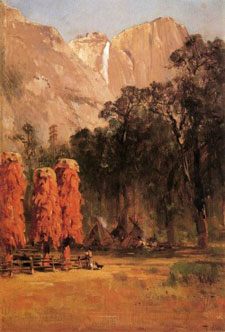

Yosemite's Indians, Animals, And Painter Thomas Hill

Join Tupi In This Classic Children's Story

Tupi The Chipmunk Childrens Book And Now For Kindle

Bill Berry's Prints Return

Yosemite Wildlife Activity Book Now Also For Kindle

Yosemite's Artist Thomas Hill...The Days Of The Indians In Color

Cowboys And Indians In Yosemite A Book And For Kindle

Stories Of Cowboys And Indians