Deer Kill! How A Coyote Pack Tracks And Kills...

Deer kill is an account written for the Yosemite Nature Notes series of publications. It was written by Yosemite Rangers after the discovery of the remains of a large mule deer buck that had been killed by coyotes.Deer and coyotes are natural enemies…but rarely will coyotes successfully attack a full grown buck.

Many people are not aware that besides the antlers,(that are an obvious

means of defense for the male), the hooves are sharp and are used very

effectively by both of the genders.

The additional reach that is gained when kicking is also a good way to keep enemies at a distance while under attack.

“Feast

on The Grapevine” is the account of two Yosemite Rangers and their

forensic work after discovering the remains of a dead mule deer buck on

the Grapevine section of the Wawona Road.

Big and healthy while alive, the question was how did he die and how many coyotes were involved.

The signs of coyotes were everwhere…see what the Yosemite Rangers concluded from what they found...

Yosemite Nature Notes

For nearly 40 years Yosemite Nature Notes served the park and the National Park interpretive program.

First mimeographed as a newsletter in July 10, 1922 “Nature Notes evolved into a small booklet containing interesting Yosemite themed articles and was produced monthly.

The little publication was read in its various forms through the years by millions of park devotees.In its more than 400 regular issues and 23 special issues can be found much of the story of Yosemite National Park-its human history, archaeology, biology and geology.

Revenues from Yosemite Nature Notes were dedicated entirely to assisting the park naturalist division in the furtherance of research and interpretation of the natural and human story in Yosemite National Park.

“Feast On The Grapevine” was written by John T. Mulladay, Yosemite Park Ranger, and appeared in the March 1956 Issue of Yosemite Nature Notes.

Escape

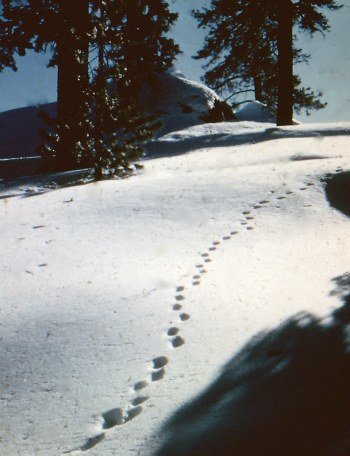

The heavy-antlered mule deer buck bounded through the cold darkness of the early winter morning. The ice encrusted brush of Turner Ridge offered little resistance to his massiveness as he crashed headlong through it.

Nor did it slow the yelping, gray-coated coyotes running in swift pursuit, their bellies fairly skimming the frosty cover of bear clover.

A short distance more and the deer would reach the clearings of the South Fork of the Merced where the open flats would afford room for a full grown 180 pound deer to attain top-speed flight and, if necessary, afford the space to swing his sharp-pointed antlers and kick his razor-sharp hooves in a frantic defense against an inevitable attack.

The car rolled cautiously up the snowy Grapevine Grade of the Wawona Road. Tire chains and the snaking curves of the icy roadbed made higher speeds unsafe. Yosemite Valley and its welcome lodging still lay over 25 wintery miles ahead.

The beams of the headlights shown through the mist of low lying mountain clouds; first finding a displaced rock to be avoided; next a road sign offering advice or information.

Pursuit

The buck, fearful and excited, hesitated on the brink of the bank. Two leaps more and he would be down and across the main trail…but he was dazzled and confused by the blinding lights coming toward him! The clanking racket of steel tire chains against the macadam! The yapping of the closing coyotes! What would he do?

Down the bank he went and his hooves met the icy hardness of the road and slid. Tire chains scraped and dragged across the same icy hardness in a frantic effort to bring the car to a halt.

In spite of the panicked, last minute swerve of the drivers wheels the big buck did not escape. Death came suddenly on the Grapevine at that early morning hour.…The car resumed its journey onward.

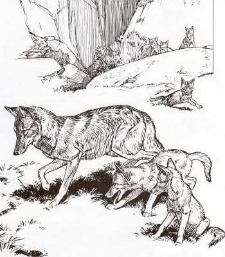

Capture

The Coyotes waited impatiently on the brim of the cut until the red lights and the noise faded away . Now to the feast! Coyotes, large and small, tore at the warm deers hide, exposing the firm flesh. Their bellies soon became gorged.

As they ate, one satisfied animal would waddle away from the bloody lifeless form on the road only to be replaced at the carcass by a new tawny form loping in from the surrounding wilderness.

The telegraph of the wilds was far-reaching and response to its message was rapid.

Before the sun bathed the pines of the hills the next morning the flesh of the full-bodied deer buck had vanished before the appetites of the many snarling, snapping coyotes.

By the time the full morning had dawned there was little left to be torn from the remaining hide and bones.

A few shreds of flesh might have been cleaned from the deers bare skeleton but by then, only by gnawing. And they were gorged, what satisfaction would a few shreds yield to full bellies.

Slowly and with greedy reluctance the dog-like animals wandered off, alone or with families, to seek a sunny granite bench for a long day of contented leisure.

Discovery

This is the story of a midnight feast as Ralph Jessen (seasonal ranger and old-timer) and I pieced it together on that Sunday morning in December.

Perhaps it is not an unusual story, for many deer are killed outright by automobiles, and others are critically injured. Often, as in this case, the deer satisfies the hunger of coyotes and other carnivores.

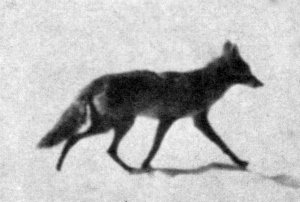

Coyotes will usually not attack full grown and healthy deer, they prefer instead individuals already weakened by disease or injury. Even a concentrated attack by a group of coyotes would not assure a meal of venison if the deer was in good physical condition to retreat or fight.

Ranger Jessen and I feel, however, that this story is unusual and important with respect to the number of coyotes which were present. The evidence was there on the road, and we examined it carefully.

Remains

The carcass of the deer buck as we found it, was stripped of practically all of its flesh. Only the head (with the exception of the fleshy tip of the nose) was intact.

His symmetrical four point antlers were massive, possessing a spread of 18 inches. The now limp hide had not been torn haphazardly from the body by the coyotes, but had been ripped open from the belly side.

The entire skeleton was intact, the bones still articulated. The entrails were gone, and the flesh of the neck had been removed by way of the body cavity. The cape of the hide had not been torn.

From the size of the antlers, the head, and the hooves as well as from the general appearance of the hide, Ranger Jessen and I concluded that this deer must have weighed around 180 pounds alive.

This agrees with known weights of similar deer bucks killed along adjacent park boundaries. The hide was in fine, sleek condition indicating a healthy individual.

The time of the accident was not more than 6 hours prior to the discovery of the mule deer carcass at 8 a. m. This estimate was based on freshness of the blood, suppleness of the hide in spite of the freezing weather (17 degrees at South Entrance) and by questioning local travelers who had used the road that night.

When we found the remains of the buck he was still in the middle of the road, and what remained did not exceed 50 pounds. There was no evidence that any quantity of flesh had been carried from the scene; and the fact that the skeleton was complete would indicate that this had not been done.

If our estimates are correct, about 130 pounds of meat was devoured on the spot within a time-frame of six hours. It was likely that the meal took much less time.

An Explanation

Upon returning home, two references were found in the literature regarding food capacity of coyotes.

J. Frank Dobie, on page 160 of his The Voice of the Coyote

(Boston, 1949), gives the report of a trapper who examined the stomach contents of a female coyote which had just killed a lamb. He reported that it contained "five or six pounds of select meat."

Joseph Dixon, noted for his meticulous wildlife observations, reported in the Journal of Mammology (6:1, p. 41): "I have ... been able to determine how much food constitutes a square meal for each species in the wild . . ." For the coyote it was 791 grams (1.74 pounds) or the equivalent of two ground squirrels.

Grinnell, Dixon and Linsdale in The Fur Bearing Mammals of Califorina (Berkeley, 1937) states by comparison that stomach records show that from 5 to 8 pounds of meat is a large meal for a full-grown mountain lion.

A scientific authority has told me that he would not expect an animal the size of a coyote to be able to consume more than 1/10 of his weight in fresh meat at a single meal. A state trapper, working on lands adjacent to the park, felt this figure to be sound.

On this basis we could reason that a mature mountain coyote with an average winter weight of about 40 pounds (Grinnell, Dixon and Linsdale, op. cit. ) would not be able to devour more than 31/a to 4 pounds of meat during the course of an uninterrupted meal. This perhaps could be stretched to 5 pounds if he were really hungry.

25 Coyotes

At least some of these coyotes had fed on other venison within the previous afternoon and evening. No less than 10 large piles of their droppings were found on the road along the road shoulders at the scene. Deer hair was much in evidence in all of the scats, and it is unlikely that this represented food digested at that meal.

Those are the facts. How many coyotes fed on this mule deer? Who knows for sure? It may seem a fantastic number but the evidence indicates that no less than 25 of them gathered to participate in the grisly feast on the Wawona Road that cold December morning.

To return to the Home Page from Deer Kill please click here.

Yosemite Animals Activity Book...Meet The Furry Friends

Yosemite's Furry Friends. Activity Book Or Kindle

Bill Berrys Yosemite Prints Return

Yosemite's Mule Deer

Yosemite's Mule Deer Doe and Fawn

Yosemite's Mountain Coyote

Yosemite's Mountain Lion

Yosemite's Black Bear

Yosemite's Black Bear Mother And Cubs